The article of the month

This Month… by Teresa Caldecott Cialini

We are celebrating the feast of Saint Luke this month (on the 18th), the Evangelist with whom we have been spending so much time during Year C in the cycle of Sunday Gospels. At this point in the year, we have reached some challenging statements on the themes of faith and humility from chapters 17 and 18:

“If you had faith like a grain of mustard seed, you could say to this mulberry tree, ‘Be uprooted and planted in the sea,’ and it would obey you” (Lk 17:6). “When you have done all that you were commanded, say, ‘We are unworthy servants; we have only done what was our duty’” (Lk 17:10). “When the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on earth?” (Lk 18:8). “Everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, but the one who humbles himself will be exalted” (Lk 18:14).

In these chapters of Luke, Christ is on his final journey to Jerusalem (somewhere between Samaria and Galilee in the north, heading southwards), and in this stage of his earthly ministry the tone becomes increasingly urgent and eschatological. The various threads of his teaching, played out in Luke’s sophisticated narratives through encounters, healings, and parables, are woven together around the central call to preparedness.

You will find an evocative painting of this fascinating Evangelist in our Art Enclosure this issue, by Valentin de Boulogne, displaying a few of the notable characteristics of, and traditions surrounding, this patron of artists. Though we only have a few clues about who Saint Luke was, the evidence from his writing style and other contemporary mentions of him point to a cosmopolitan, highly educated figure. It is thanks to him that we have the fullest birth narrative and many uniquely preserved, well-loved parables—not to mention the stories of the early Church and missionary activities of the disciples contained in the Acts of the Apostles, which he also penned.

Missionaries of Various Kinds

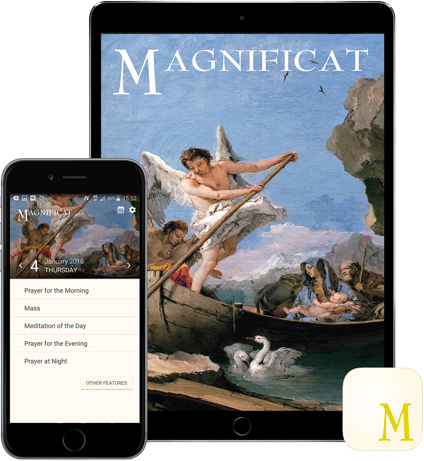

On Sunday 19th we celebrate World Mission Day. The theme for 2025 is “Missionaries of Hope Among all Peoples”. Saint Luke, and the Apostles Simon and Jude (28th October) are some of the earliest examples of Christian missionaries, of course: while the former spread the Good News of Jesus Christ through his writings and his accompaniment of Saint Paul, the two Apostles travelled to many places (some traditions suggest even Roman Britain) before giving their lives as martyrs in AD 65. But there are other less obvious patrons of this theme in this month’s calendar, not least Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, whom we celebrate on the 1st, and who is depicted on our cover. Like Saint Teresa of Jesus (15th October), who tried to run away to join the missions as a young girl, Thérèse longed to be a missionary herself from a young age but came to realise God was calling her to partake in that work in another way. Though enclosed in a convent for her whole, short adult life, Thérèse was such a determined spiritual sister to missionaries through prayer, sacrifices, and letters, that she was declared the universal patroness of missions in 1927, two years after her canonisation.

In contrast, Saint Francis of Assisi (4th October)—remembered for preaching to animals and praying on hillsides in the popular imagination—did, in fact, take himself off on two dangerous missions to the Ottomans, the second time gaining access to Sultan Malik al-Kamil in the Holy Land during the Fifth Crusade. A contemporary of Saint Francis wrote that the Sultan came to respect this “Man of God” through their conversation but feared the impact on his military position should his men start to convert and so sent Il Poverello respectfully back to his Christian brethren.

Prayer and the Spark of Hope

To be a Christian missionary is not to simply spread a set of interesting stories or a collection of rules, but to be so overflowing with hope that we have to share it with everyone. In his message for this year’s Mission Sunday, the late Pope Francis reminded us, echoing Saint Thérèse, that missionaries of hope are men and women of prayer. “Let us not forget that prayer is the primary missionary activity and at the same time ‘the first strength of hope’.”

The Gospel of Luke emphasises more than any of the gospels the centrality of prayer, demonstrating this through key moments in Jesus’ life: before his baptism, choosing the Twelve, at the Transfiguration, and in Gethsemane. Luke also records major, explicit teachings on prayer, not least highlighting the Our Father as a learned, communal practice, showing how it enables participation in the Trinity by orienting the participant towards the Father and inviting the indwelling of the Holy Spirit. Two of the Sunday Gospels this month approach prayer from the angles of both petition and praise through the story of the healing of the ten lepers (Sunday 12th) and the parable of the persistent widow and the unjust judge (Sunday 19th).

Whether we are praying to ask for guidance, assistance, in thanksgiving, or to reorient our activities, the theological principle of hope is the foundation. Christ tells us—and shows us—how prayer must be persistent, trusting, and humble. It is not a transaction but a relationship, inspiring a hope that is concrete rather than abstract. This is the kind of hope that inspires missionaries. “By praying, we keep alive the spark of hope lit by God within us, so that it can become a great fire, which enlightens and warms everyone around us, also by those concrete actions and gestures that prayer itself inspires” (Pope Francis, “Missionaries of Hope Among all Peoples”).