Request sample copy(ies)

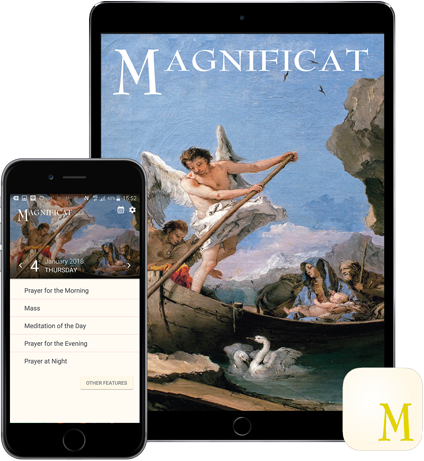

Magnificat is a spiritual guide to help you develop your prayer life, grow in your spiritual life, find a way to a more profound love for Christ, and participate in the holy Mass with greater fervour.

Magnificat is a monthly publication designed for daily use, to encourage both liturgical and personal prayer. It can be used to follow daily Mass and can also be read at home or wherever you find yourself for personal or family prayer.

Every day, in a convenient, pocket-sized format, Magnificat offers beautiful prayers for both morning and evening inspired by the treasures of the Liturgy of the Hours, the official texts of daily Mass, meditations written by spiritual giants of the Church and more contemporary authors, essays on the lives of the saints of today and yesterday, and articles giving valuable spiritual insight into masterpieces of sacred art.

See below based on the country where copies should be sent.

Please include your full name, address, the preferred month to be received, and what the copies will be used for.

For request to be sent in the UK :

Please contact the Catholic Herald at uk@magnificat.com

or call +44 (0)20 7448 3607

For request to be sent in Ireland :

Please contact the Irish Catholic at ireland@magnificat.com

or call +353 1 6874020

For any other countries :

Please email magnificat.promo@magnificat.com

We cannot guarantee delivery of copies. Based on availability.